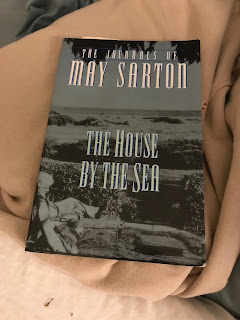

photo by Anna Reavis

“I

couldn’t let myself believe it...and also go on breathing...”

When I first heard of

Wild by Cheryl Strayed, I wanted

to read it: walking alone on the Pacific

Coast Trail to try to outwalk the ghosts of your past and the pain inside you sounds

like something I would do or would have

done, had I been childless at anytime in the past 20 years. So

last week, when I found it at my small local library, I grabbed it up and put Les

Miserable on hold.

I had no idea how hard just getting through the first

chapter would be for me. That’s where I

got to last Friday before I had to stop and regroup and decide if I was strong

enough at this point in my life to read this woman’s words. I thought I was getting a hiking memoir. What I got in the first chapter instead was a

reliving of my own mother’s death. Strayed

lost her mother in the same way that I lost mine (except that I was pregnant

with my first child at the time) and at exactly the same time in her life. She had the same kind of intertwined, how

could I live without this woman, relationship with her mother that I had with

mine. I even remember struggling to stay

awake with her nights, which is almost impossible in pregnancy, because I was afraid

she would die while I slept, and then feeling guilty that I fell asleep. The biggest difference is that I was with

her, holding her hand, when she died, a

type of fullness and completion denied to Strayed, and for which I have been

infinitely grateful because being present at the moment of death had been

denied me when my brother had died a few years before, so already I knew how

important it was. It brought to mind Sally Field’s speech in Steel Magnolias about being present when

she brought her daughter into the world and being present when she went out of

it. This was the one person I knew who

had been present when I came into the world.

I’d be damned if I wasn’t going to be there when she left it, no matter

what was going on with my body at the time.

The one big other difference is that I have never tended,

nor even been to her grave. I suppose

that is a kind of denial: denial through

ignoring; close your eyes, and it isn’t there. So because I have lived 20 years now in my

self-inflicted forgetting, being surreptitiously

overwhelmed with this issue in a hiking memoir completely took me aback. Here

are some of the last words of the first chapter: “Nothing could ever bring my mother back or

make it okay that she was gone…It broke me up.

It cut me off. It tumbled me end

over end…I would want things to be different than they were. The wanting was a wilderness and I had to

find my own way out of the woods.” What

motherless child can read words like these and still breathe? I think I am going to have to make myself

finish this book. Twenty years is long

enough to live in forgetting.