Saturday, June 27, 2009

Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling

Thursday, June 18, 2009

A Little Whitman for a Bad Day

and self-contain'd,

I stand and look at them long and long.

They do not sweat and whine about their condition,

They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins,

They do not make me sick discussing their duty to God,

Not one is dissatisfied, not one is demented with the mania

of owning things,

Not one kneels to another, nor to his kind that lived thousands

of years ago,

Not one is respectable or unhappy over the whole earth....

Walt Whitman

Saturday, June 13, 2009

Two novels by Sarah Dunant

Recently I have read two novels by Sarah Dunant: The Birth of Venus and In the Company of the Courtesan. The first novel is set in Florence during the Renaissance, and the second in Venice during the mid 1500s. While I learned some history and other interesting and unusual facts from both novels, I did not love either one. Both times, at about the midpoint of the book, I wasn’t sure I was going to finish. I’m not sure why, but neither book really captured me. I liked The Birth of Venus better just because I enjoyed the plot more. In the Company of the Courtesan had too much personal detail about the life of a courtesan and about the relationships between men and women. (Guess the title should have been a hint to me--duh.) Both novels did a good job of making me feel like I had been to another time and place.

Some of the interesting facts I learned from the novels:

Wealthy Florentine families had their own chapels in their palazzos, and they hired artist (some famous and some not) to paint frescos in them.

I learned about how frescos are painted, which I am not going to explain here.

In order to keep the family wealth intact, only the first son was allowed to marry. His new family stayed on in the family palazzo, and the family wealth and business were his. The other sons had choices including: university studies for law degrees, military service, and the priesthood, among others. I guess this surfeit of unmarried, perfectly healthy men explains the thriving courtesan trade.

Florentine families could only afford dowries for their first and possibly second daughters. One of the other daughters might be allowed to stay at home and serve as the governess for her married brother’s children. The other daughters were sent to convents with or without their consent.

Noble girls and women were not allowed to go outside unattended. They were not allowed to speak to unrelated men except in family-controlled situations.

Women were not allowed to be artists, regardless of their talent, but there was at least one situation in which a nun painted the fresco in a chapel at her convent.

In 1528, Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, sacked Rome. Many Romans fled to other Italian cities as refugees.

Venice was built on islands in a lagoon and has a combination of canals and alleys cutting through it. A fondamenta is a street beside of a canal.

The Jews in Venice were confined to a ghetto and were used as bankers by the other Venetians.

Venice called itself the most serene republic, La Serenissima. It was ruled by nobles, who elected a leader called a doge. The doge was a noble. He ruled at the pleasure of the nobles until he died. To prevent one family from becoming the ruling family, when a doge died, his family was excluded from the next doge election. The laws of the republic were enforced by the Council of Ten, which consisted of ten judges, the doge, and some noblemen. They tried, convicted, and sentenced anyone accused of breaking laws. Some of the laws regulated political and religious beliefs, so some people were executed for being on the wrong side of the government and/or the church. Sometimes people were executed by drowning.

The doge lived in the Doge’s Palace, where the government meetings, including trials, were held. The prison holding accused criminals was also in the Doge’s Palace. Along the outside facade of the palace are many statues. One of the statues in the palace is a lion with his mouth open. If a citizen wanted to accuse another citizen of breaking the law, he could write his accusation on a piece of paper and put it through the lion’s mouth.

Venice served as a way-station for trade between east and west for many years. This made her a rich city, but with the discovery of a trade route around Africa, her importance and wealth began to wane.

Thursday, June 4, 2009

The Silver Pigs by Lindsey Davis

Tuesday, June 2, 2009

Brunelleschi's Dome by Ross King

Sometimes, upon reading the last sentence of a book, I feel like I need to start again at the very beginning. In the case of Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture by Ross King, so much new-to-me information was presented that I feel like I don’t remember even a tenth of it. One of the more straight-forward new pieces of information was that the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in

Brunelleschi was a clockmaker and goldsmith, turned amateur painter, sculptor, and architect. His father wanted him to be a notary. Maybe father doesn’t always know best. He built a model for the dome and won the competition to build it but didn’t have any recorded plans of how to build it. The dome would be massive, on a scale of things just not done at that time. Before even beginning on the dome, Brunelleschi spent 13 years, off and on, in

Eventually, Brunelleschi begins to work on the dome. He will build two domes, nested one inside the other, without using the traditional wooden centering scaffolds. The masons he hires will be expected to supply their own tools, their own food, and their own drink everyday. Depending on how high up they are working, they will either be drinking wine or watered-down wine. God knows I would need wine to work up that high. At least then you might not know if you fell. They will not be allowed to descend during the day. Brunelleschi will also be responsible for managing these myriad men without the convenience of standardized time – so no punching in and out. Some of these men will die on the job – no OSHA, no workers comp, no health insurance benefits. You get hurt, you and your family don’t eat. None of them, including Brunelleschi, really knows if what they are doing will work.

Brunelleschi had to invent and build the lifting devices (hoists and cranes) he needed as the job progressed. He had to intuit this knowledge. The ancients had known these maths, but they had been lost during the Dark Ages and were not rediscovered until after he had already built his machines. His hoists and cranes outlived him. They were not removed from the dome until after his death. In addition to the machines, he somehow figured out to lay the bricks in a herringbone pattern so that one row would support another as the bricks were being laid, and he had the dome built with a nine-tiered circular skeleton as support. Even after the dome was finally completed, a massive lantern for the apex had to be designed and built. This lantern required a different kind of hoist, which, of course, Brunelleschi invented and built. The book has a great section describing how this lantern was used as a giant sundial and how the knowledge gained from this use improved navigation maps that were used by Columbus, but you’ll have to read the book to get all that. I’m too tired to interpret it for you.

At the end of the book, Ross King writes, “Indeed, in height and span the cupola of Santa Maria del Fiore has never really been surpassed…. Not until the twentieth century were wider vaults raised, and then only by using modern materials like plastic, high-carbon steel, and aluminum….” (p163)

And all this was accomplished by a short (5’ 4”), ugly, stinky, uneducated, secretive, suspicious, petty little unassuming Florentine man. Short people rule.

A Kind of Healing

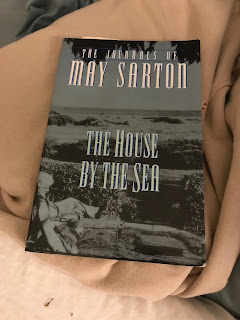

"...to live the slow quiet rhythm of a day as a kind of healing" Several years ago, I discovered May Sarton’s journals. What a b...

-

photo by Anna Reavis "I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and...

-

photo by Amy Brandon "You are privileged to read these words so many are barred from. And why are they barred? Because the Nazis...